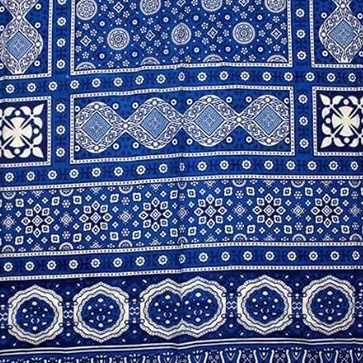

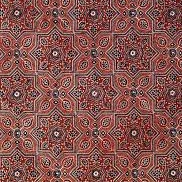

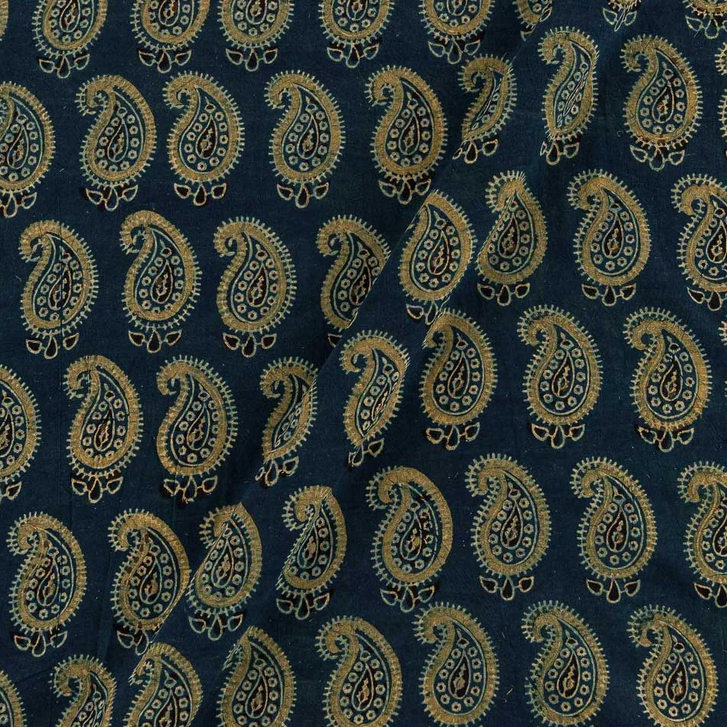

Ajrak derives from the Sanskrit term "A-jharat," meaning "does not fade." In Arabic, Ajrak signifies "blue," one of the craft's primary colors. Another interpretation suggests that Ajrak originates from the Persian words ajar/ajor (meaning "brick") and -ak (meaning "small"), referring to the block printing technique used to create patterns on cotton fabrics.

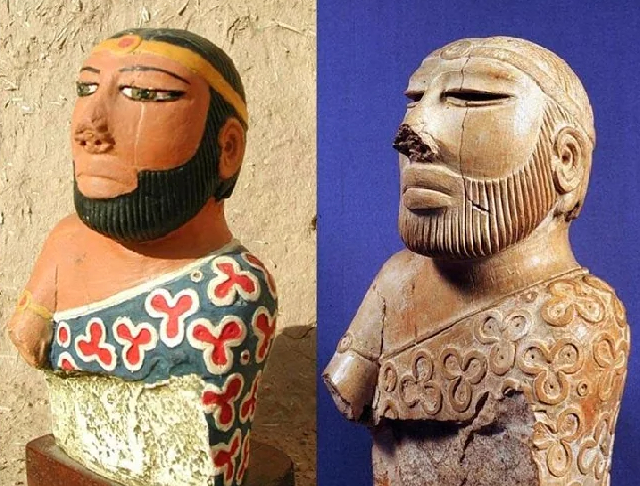

Block printing is a traditional craft of the Indus River Valley. Despite the political and cultural divide between India and Pakistan since 1947, this shared heritage thrives in Pakistan's Sindh province and India's Kutch district.

For the Sindhi people of Pakistan, block-printed fabrics are ubiquitous across cities, villages, and nomadic settlements. Men wear them as turbans, belts, or draped over their shoulders, while women use them as dupattas (long scarves) or shalwars (loose trousers). Sometimes, the fabric even serves as makeshift swings or hammocks for children. Ajrak garments are worn at weddings, cultural events, or gifted as tokens of hospitality and respect.

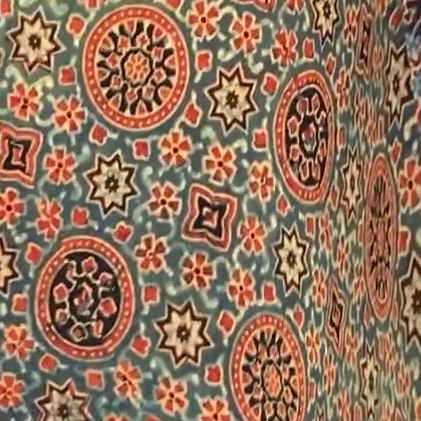

Image/ Block printing is an important traditional attire in Sindh, Pakistan.

Source/ affordable.pk